Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

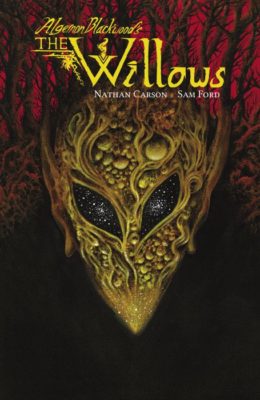

Today we’re looking at Nathan Carson and Sam Ford’s adaptation of Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows”. Issue 1 came out in November 2017, and #2 will be out in February (not June as originally reported). Spoilers ahead, but minimal for #2.

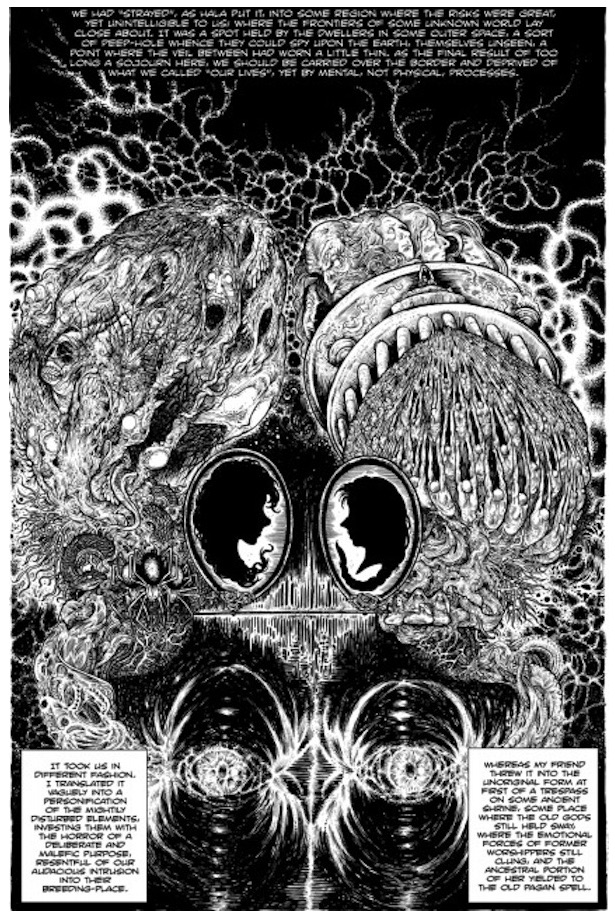

“We had ‘strayed’, as Hala put it, into some region where the risks were great, yet unintelligible to us; where the frontiers of some unknown world lay close about. It was a spot held by the dwellers in some outer space, a sort of peep-hole whence they could spy upon the earth, themselves unseen, a point where the veil between had worn a little thin.”

Carson and Ford’s take on Blackwood’s classic is remarkably close to the original, so we can rely on Ruthanna’s fine summary from last week for all but small deviations in plot. The big change lies in the central characters, who are now:

Opal, age 25, born into the British aristocracy but wild in spirit. Her early marriage to an older man ended in early widowhood and a sizeable inheritance that secured her financial independence and the freedom to roam.

Hala, age 29, a stoic Swedish woman raised in a family of fishermen. As big and strong as her brothers, she worked every bit as hard. With her hardiness, skills and keen intellect, she considers herself the equal of any man.

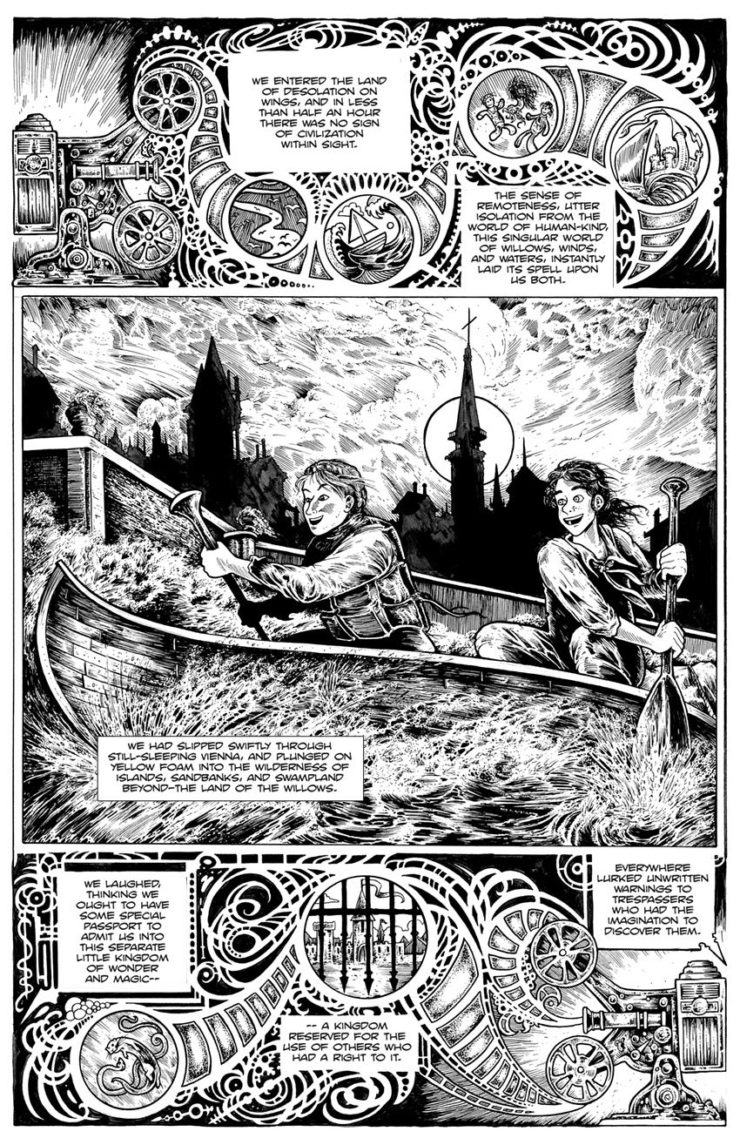

The year is 1907. Beyond gay Vienna, between the towns of Pressburg and Komorn, the Danube flows through a desolate region of tangled channel, shingle beds, ever-shifting sandbars and willows. Mile after mile of low, huddled, wind-tossed, whispering willows….

What’s Cyclopean: Much of the comic’s language is drawn from the original; the pictures themselves are well worth their thousand words.

The Degenerate Dutch: Carson and Ford work around some of Blackwood’s issues, giving “The Swede” an actual name, and wilderness skills without reference to any ethnic stereotype.

Mythos Making: Blackwood’s powers presage Lovecraft’s elder gods; Carson and Ford envision those powers beautifully influenced by a century-plus of cosmic horror.

Libronomicon: Books still too wet to read this week.

Madness Takes Its Toll: With so much cut down to dialogue, and less internal monologue, questions arise more starkly about the sanity of Opal’s own reactions.

Anne’s Commentary

Some of the high unholy days of my youth were when the new Creepy, Eerie and Vampirella magazines hit the newsstands, or rather, the rickety rack in the dim-lit rear of the variety store a few blocks from my Catholic grammar school. I was always tapped to nab the loot because I wasn’t (too) afraid to buy flagrant trash right out in public, wearing my scratchy plaid school uniform, and was the tallest of our gang. I could pass for, like, thirteen. My strategy was to brazen it out and put Vampirella on TOP of the pile.

Not that the old guy at the cash register cared—the nuns, on the other hand, would have sentenced us to ten consecutive Stations of the Cross for fouling our impressionable young minds with those bimonthly feasts of gore and demonic imagery and lewd speculation on how Vampy’s iconic jockette straps could contain even the most supernatural boobs.

Which is all by way of explaining the nostalgic thrill I enjoyed poring over Carson and Ford’s “Willows.” This adaptation reminded me of the best stories from the Warren horror mags, the ones in which both art and story shone with the refulgence of skulls under a full wolf moon. Except, as a faithful rendition of the source material must demand, their “Willows” is considerably more sophisticated.

Out of the gate Carson and Ford earned my respect for merely tackling Blackwood’s “Willows.” As some readers noted last week, it’s a tale that may require a certain patience, a certain maturity of palate, before its full glory can be appreciated. Like the noblest Bordeaux, you know, or Brussels sprouts. Okay, the Bordeaux, then. The potential for visual and visceral impact is there, is vast, but it’s no easy catch. It’s complex, as shifting and wind-confused and maddeningly ephemeral as the willow-realm itself. You can’t trample it to submission with bullish declarative sentences: Listen—this is what happened! You can’t slap your canvas silly with broad strokes: See—this is what it looked like! Not I couldn’t enjoy kids whispering around a campfire: “See, these two guys took a canoe down this river, into this swamp, right? Where it was all sandy islands and willow bushes, no people, and everyone warned ’em, there’s like aliens there, or monsters or something, and nobody comes out the other side. NOBODY. But they went anyway….” If EC Comics’ Crypt Keeper should present that story with pulpy panache, that too could have its pleasures.

But Blackwood’s story is the polar opposite. How might a comic writer compress his luxuriant (some might snark excessive) prose into a script of reasonable length without turning the supremely alien OTHERNESS impinging on our world into just another tentacle poking through a veil? How might a comic artist capture not topography, not scenery, but an atmosphere of building dread—because it’s this aspect of Blackwood’s “Willows” that puts it in the Pantheon of horror.

Given a lot more space, I’d go into the big change of the central characters from two unnamed men, probably middle-aged, apparently unattached beyond strong comradeship in adventuring arms, to two women, in early adulthood, apparently in the early stages of romantic attachment. Given a social period hostile to female independence and homosexuality in general, I’m curious about their backstory, how they met, how they’ve managed to overcome family and practical obstacles, the added problem of Hala’s lower social class, especially with regards to education (she seems very well read for a fisherman’s child of the day.) No room for all that in the comic, I know. Blackwood gets away with his Swede’s fairly abrupt erudition by being vague about his background. We may assume the Swede is Narrator’s social inferior, even his servant, but we don’t KNOW he’s any less educated than Narrator.

In the end, regarding the comic, I accept Hala and Opal as presented, which is the important thing. I feel the added intimacy of their relationship and respond to their shared danger with added tension.

What I want to get back to are the questions I asked a couple paragraphs back. I won’t prolong the suspense, though I doubt I’ve left you in any. Carson and Ford have both succeeded in their epic tasks. The hows? Oh man, to address the hows, how many days do you have? And do I get a Ph.D. in Really Deep Aesthetic Analytics when I turn the thesis in? Here’s the short version instead.

Hold on.

This is seriously profound, I’m not kidding. You should maybe put that coffee or soda bottle down to prevent any unfortunate spit-take action.

(This is it, next.)

THE WORDS AND THE ART WORK TOGETHER, AND THE SUM IS GREATER THAN THE PARTS!

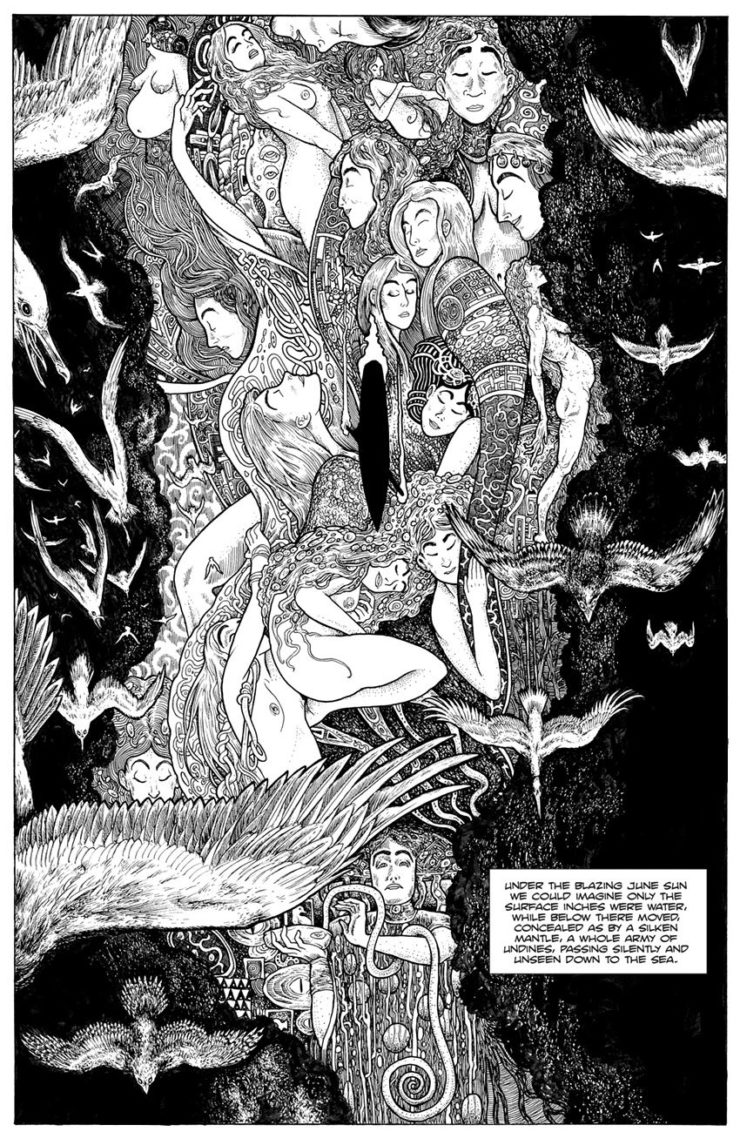

Examples: An early sequence of panels shows Opal and Hala laughing as they pass through Vienna at dawn; then a white heron; then moon, fireside, tent, peaceful talk; then excitement over a whirlpool; then text about the varied song of the Danube that culminates in the first brilliant “set piece” of the comic,” the full page panel of the “Undines, passing silently and unseen down to the sea.” I could look at this page forever, a Klimt-like stream of water elementals in every age of womanhood from pubescence to crone, overflown with Audubon-accurate birds of sea and interior. I would have this tattooed all the way up my arm, except I’m not much for the needly thing. Can I just have it embroidered on my high priestess robe? Love!

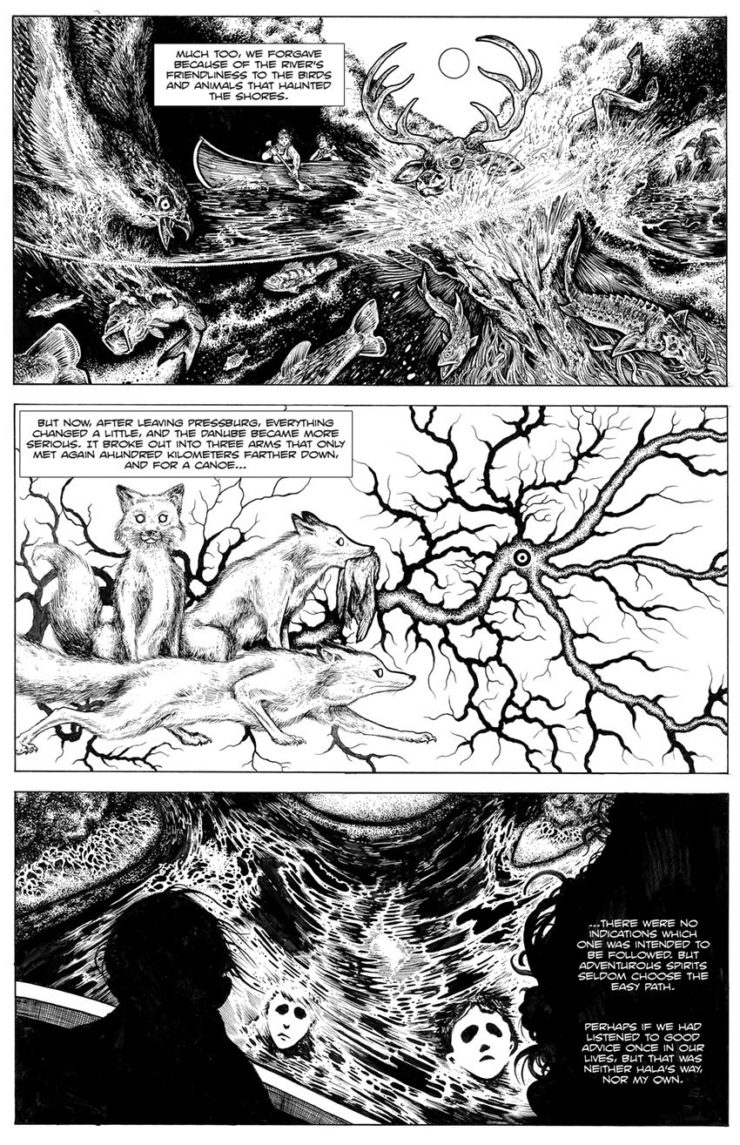

Sorry, distracted. Next in the sequence. The “friendly” animals and birds that beguile Opal and Hala from any disquiet about the Danube. Except the panel, closely inspected, shows that fish hawk sinking talons into a bass and the leaping stag framing the sun between his horns in a way that can only be an omen. Of something….

Next, as the text tells us about the Danube breaking into three arms, we don’t get a literal interpretation of the words, a picture of the river branching. In fact, the picture might seem to have nothing to do with the words. It shows three foxes, one staring directly at the reader, one holding prey in its mouth, one slinking along the ground. Behind them is what at first appears to be a leafless, twiggy branch. Wait. I can hardly stand how spot-on this is. That branch, with its central “eyespot,” is really a neuron! The Danube is a nerve in a vast organism. Vaster than the Earth? And those foxes are creepy, not friendly at all. Their eyes are practically white. White eyes, uh uh, that’s not right.

Final panel in sequence? Opal, in text, wonders: What if we had listened to good advice once in our lives? In illustration, she and Opal, in silhouette, gaze into troubled water, where their reflections appear as white masks with black sockets for eyes.

Room for only two more panels out of a hundred I could mention! In the second part of “Willows,” Opal is napping after their first uneasy night on the island. In text, she realizes: “The wind held many notes, rising, falling, always beating out some sort of great elemental tune. The river’s song lay between three notes at most, and somehow seemed to me, to sound wonderfully well the music of doom.” Ominous words, Blackwood’s, a good concise choice for this point in the comic. Ford amplifies the music of doom admirably, again with an unexpected image that then renders itself so “of course!” The bottom of the panel shows Opal fetal-curled, swarmed by phantom G-clefs, F-clefs and quarter-notes. The top of the panel shows the scene outside the tent, the river and the willows and the sun shining. Oh, and a gigantic snake, black and gleaming like the Danube, slithering toward two tiny rodents fetal-curled together in the too-little-concealing brush.

Last, and most impressive conceptually, is the full page panel that appears when Hala and Opal start arguing about what exactly troubles the willow-island, their shrinking refuge. They agree they’ve inadvertently entered the vicinity of a thinning between worlds or realities, ours and—theirs. But they can’t agree who They may be. Carson manages to get it down to Opal thinking that she personified the Dwellers from Outside as personifications of the mighty elements, disturbed by human intrusion, whereas “less original” Hala personified them as the Old Gods still holding sway where the emotional forces of their former worshippers still clung, bless her pagan soul. Over to you, Ford. Illustrate that. And he does, managing, for me at least, to carry words, thoughts, farther. Centered in the panel are two miniatures, in black silhouette, of Opal and Hala, as might have been worn in lockets in the 19th century. They face each other. Beneath, as if floating in infinite space, are two vortices of energy like eyes, which send up billowing columns of images that embrace the miniatures: their conceptions of the Dwellers Beyond. Opal’s column looks like a misshapen womb bloated with hideous creatures, snakes and spiders, then monsters more and more grotesque, culminating with a dead-eyed monstrous Opal. Hala’s column seems birthed from a stalk of wyrms, twisted trees, and Norns. This blossoms into a great sphere composed of aspiring human bodies. They form the foundation of a stone temple, which is crowned with the heads of gods and goddesses, all of whom look vaguely related to Hala.

Gotta say, I’m Team Hala conceptually. Also Team Carson and Ford!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Last week, Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” made an excellent and immersive start to the new year. Carson and Ford’s graphic novel is an excellent adaptation, building onto the original framework with a modern sensibility and a deeper depiction of the central relationship. Carson respects Blackwood’s language, playing with it in key places to serve the story. Meanwhile, Ford’s Wrightson-eseque illustrations bring the setting vividly to life, shifting as fluidly as the narrator’s sense of reality.

There’s nothing like comparing two versions of a story to highlight the strengths of a medium. Last week we got lush descriptions of setting, nature memoir shading into cosmic horror, giving the same attention throughout to the emotional reactions engendered by awe-inspiring experience. This week we see the advantages of the graphic form. Realism mixes freely with symbolic diagrams, dynamic flashes of Opal and Hala rushing through swift water, and close-ups of the characters’ emotional reactions.

Key segments benefit from this visual fleshing-out. Blackwood, for example, sketches the warnings that his adventurers hear before leaving civilization—all that’s needed, for the novella. But Carson and Ford give us the intricately inked trading post, impressions that set the stage for what’s to come later. You can feel the texture of the knotted wood beams along the counter, smell the preserved hams and sausages strung from the rafters. The signs of civilization contrast sharply with the shifting whorls of the willows that lie beyond.

Later still, the half-abstract images manage the same awe-inspiring depiction of otherworldly entities that Blackwood got with words—a neat trick when you have to actually show Cthulhu. (Or the unnameable entity/entities that peer through where the veil is thin. My 9-year-old son, looking over my shoulder, was distraught at the lack of clear explanation of their nature; I was not.) In Part II, which Anne and I got to peek at, one gorgeous splash page underlines the whole threat of transfiguration by suggesting something inhuman made up of warped humanity, or the of “emotional forces of old worshippers” described by Hala/The Swede.

Carson and Ford break with the novella in their handling of the central pair: Blackwood’s unnamed-but-almost-certainly-male Narrator and stoic companion “the Swede,” versus two named women overtly motivated by a desire to escape civilization’s strictures. Blackwood’s scratchpad characterization, and ethnic shorthand, are the sort of thing you can’t (or shouldn’t) get away with in a modern story, and I enjoyed Hala’s and Opal’s relationship rather more than I did Nameless and The Swede’s. This continues in Part II, the tension between worldviews more clearly something that’s happening in both character’s heads. And it builds to the climax. I won’t spoil the small-but-important change they’ve made, since the issue isn’t due out until February, but this version of the ending is more dependent on Hala and Opal’s relationship, and more about that relationship, and as a result I found it rather more satisfying.

One final difference is the simple one of the gender-switched protagonists. Some of the implications are obvious: 1907 is a very different time for a pair of vagabond women than for a pair of men. I appreciated that this wasn’t a central characteristic for either of them, an effect of hewing as closely to the original as seems reasonable. How much do you need to change, in a story from the era before women were common in adventure stories, to have female characters be believable? Not much, as it turns out. If anything, the motivation for escape from the human world is stronger. Nameless Narrator and The Swede are out in the wilderness to have a good time and prove themselves. Hala and Opal are out there because it’s the place where they can be fully themselves. The potential loss of selfhood, the willows’ core threat, becomes even greater, knowing that the human world offers similar threats. The pair, appropriate for cosmic horror protagonists, walk a narrow line between voids.

Next week, Peter Watts’s “The Things” offers another take on the transformation of the self, not to mention the dangers of wilderness exploration. It’s a wonder readers of cosmic horror ever leave their houses.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.